In my recent post, When

Specifiers Engage in Magical Thinking, I described what happens when a

specifier believes that putting more instructions into a specification will

make for a better outcome. Never mind

whether or not those instructions were appropriate or even made sense. It turns out that dismantling an

abysmally-written specification, while useful and informative (and

entertaining), is easy. Too easy, even. Getting inappropriate language removed from

specifications is low-hanging fruit because it’s right there and we can see it

and react to it. We can explain why it’s

wrong, predict what the results will be, and then see what happens.

Far more difficult, and a more pervasive

problem, is identifying what is not stated

in the specifications, but should be.

Some specifiers believe that whatever they say in a specification will

magically make everything come out the way they want, but it’s far more common

for specifiers to believe that there will always be something somewhere in the

specifications will magically cover them for errors in the drawings and

omissions in the specs. Maybe they

believe that a reference standard includes sufficient information, or that

contractors will know the code well enough to keep them out of trouble.

Case Study

When I teach my CSI chapter's CDT class every

year, I include an example of a failure from my own history as a specifier, one

that serves as a reminder to try to query every paragraph and think about what

needs to be added.

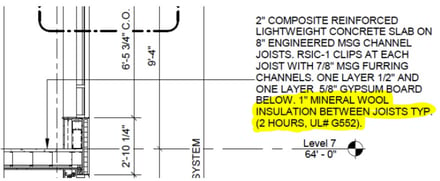

In this example, from an eight-story hotel

project, a detail indicates a floor-ceiling fire rating that is ubiquitous

throughout the project. The assembly’s UL design number

is helpfully called out on the detail:

The UL design refers to a required insulation

layer, and labels the layer “batts and blankets.” The drawing says “mineral wool insulation”

but not what type.

The specification is mostly mute about what

the batts and blankets product is meant to be.

The closest thing is a reference to acoustical fire batts in the drywall

section, meant for partitions.

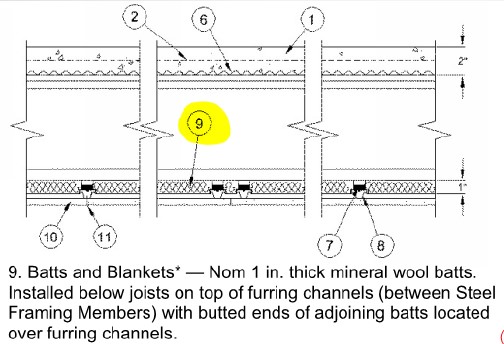

The UL design, for its part, shows the

insulation like this:

So far, the UL design and the drawing seem in

alignment, and the specifications’ omission of an actual product appears to be

a non-issue. The contractor submitted a

mineral wool blanket product for this assembly, Thermafiber SAFB.

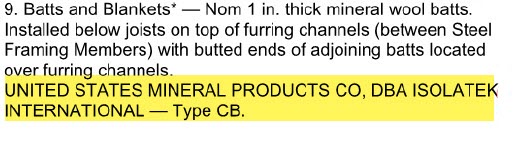

During review of the submittal, the project

architect double-checked the UL assembly and noticed something. He came to my desk with a question (I was an

in-house specifier at the time so impromptu questions were very common). The UL design had named a different product.

Isolatek CB is not a “batts and blankets”

product. It’s a rigid high-density

mineral wool board and, as Murphy would have predicted, is more expensive than

the submitted product. I don't recall

how much more, but given there were tens of thousands of square feet of product,

the gap was substantial.

The architect’s question: “Is there something

in the spec that we can use to compel the contractor to use the correct product

without incurring a change order?”

The answer we found after reading the specs, unfortunately, was “sort of, but not really.” The specifications included an instruction that fire rated assemblies be constructed using products required by UL designs. But the repetition of incorrect and vague information from the drawings to the specs ("mineral wool blankets") gave the contractor information he believed he could rely upon to buy out the project. The architect and owner chose to try to enforce the “fire rated assemblies” provision, which led to a lengthy dispute.

Lessons Learned

Being wrong is a humbling experience. Acknowledging your mistakes is hard, and changing your approach is harder.

Specifications will have omissions. That’s inevitable, no matter how diligent a

specifier is. Part of the problem is the

‘text deletion’ model of commercial guide specifications: it’s far easier to

delete something that you see and decide isn’t needed, than to add something

that’s missing. Adding relevant

information gleaned from discussions with the design team and spotted on the

drawings and extracted from reference standards or UL designs takes practice

and experience.

There’s an element of magical thinking in not specifying enough - a reliance on the belief that somewhere in that huge stack of paper is a sentence that will help me. The way to avoid this is to just do the work of deeply understanding the project requirements, and including the information necessary to achieve them, end neither less nor more than that.